Seamless, magical identity recognition

for

The world is filled with locks, keys, secret passwords, barriers. While we need these things, they are perhaps the highest-friction interaction in our daily lives. What if our technology and surroundings didn't require us to constantly tell them—or in pra

A quick note about financial case studies

The designs below are concepts that include placeholder, randomized data for illustrative purposes. Any similarity to real life events are purely coincidental. Nothing contained herein is or should be construed as investment advice, legal advice, solicitation or encouragement to conduct any financial transaction, advertising for any current or future offering of any token or security, or knowledge of a company's future token or security offering plans.

What if passwords were a thing of the past? What if our devices could respond to our presence automatically, like people do? What opportunities present themselves when we're able to consider passive signals like mere physical presence as a real first-order interaction method?

What's wrong with passwords?

Authentication is one of the most highest-friction aspects of technology, forcing users to make a trade-off between security and convenience. Signing in with strong, unique passwords is difficult—so much so that users will instead put valuable data at risk to avoid it. And tech designed to improve security, like two step verification (2SV), is even more challenging to implement and use for most users.

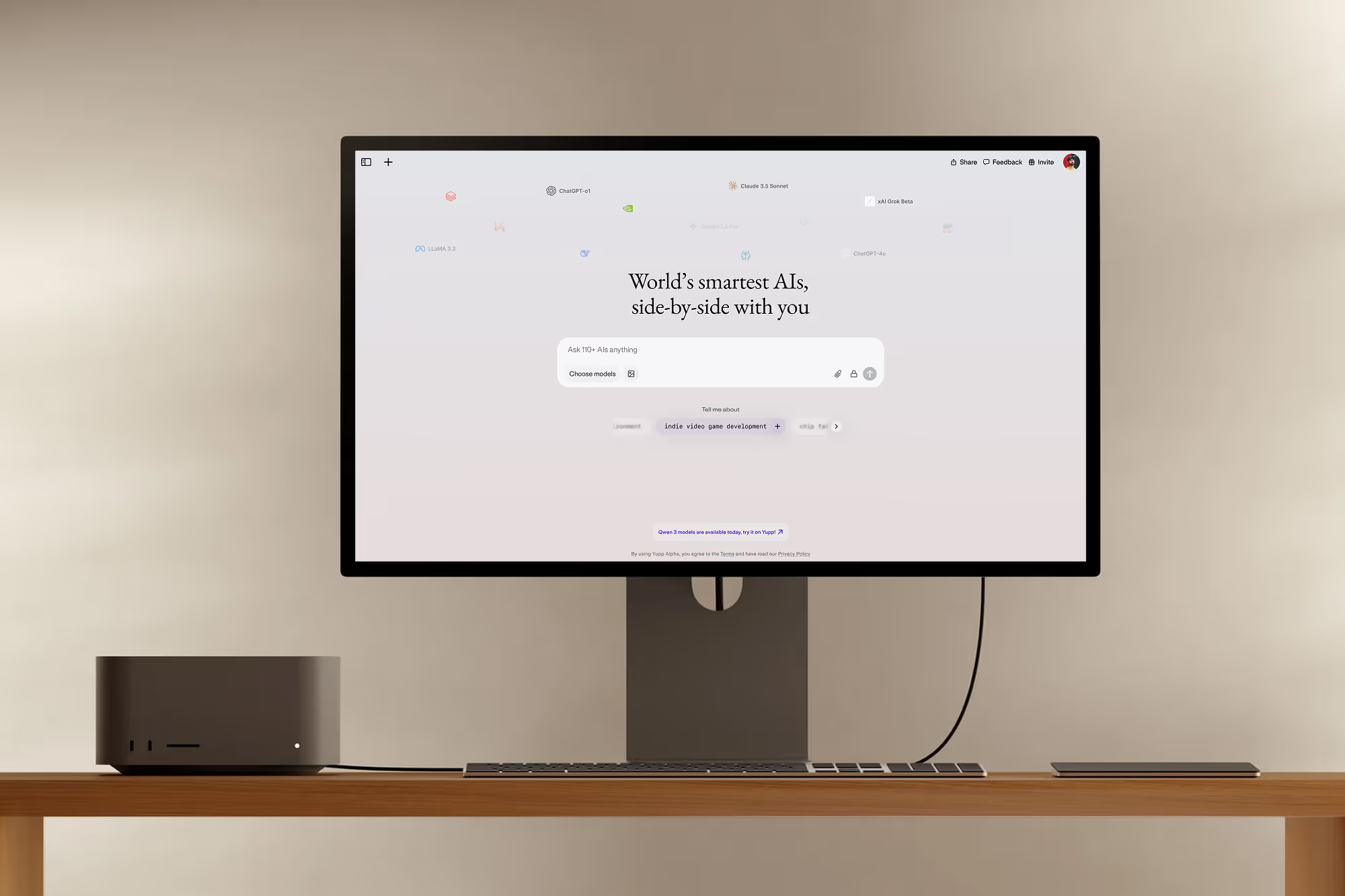

Smart Lock is a new way to think about security. It works passively in the background—like good design, you might not even notice it's there.

Your devices, like a Chromebook, unlock and lock automatically as you arrive and depart, and passwords are automatically saved in Chrome, making high security easy and seamless. And a better user experience means more than just user delight—at scale, with more users secure, the overall system is more secure, too.

Thinking beyond screens

But locks are everywhere, not just on screens. What if we could fix that, too?

Look around. The more you think about it, the more you realize how many locks we surround ourselves with. They’re all disruptive. This project made me realize what a high-friction interaction authentication is and what an opportunity there is to fix this interaction.

Consider how frustrating and even scary it would be if you forgot your password. Like many, you might take precautions—and a security risk—by writing it down somewhere. This is where Smart Lock comes in. But this is true of other locks in life too. What if you lost your house key? Similarly, you might keep a spare key to your house under a rock, just in case, sacrificing security in the process.

When you think about it, locks—in whatever form—are an unpleasant thing, and today, we’re forced to use them far more than we’d like. But we also need them more than ever.

Thinking to a future beyond screens, this friction presents an incredible design challenge and opportunity. As designers, how can we improve what it means to belong and to feel safe?

Define & Design

Next, I dove into defining and exploring the problem. What was the problem we were solving for? What would success look like? And what existing products could provide us guidance on how we might tackle this? This is often done in documentation, but as predominantly non-visual interface, this project was particularly documentation-heavy.

Another great thing about Google is how independent interns can be. Though I was an intern, I was the only designer directly working on my project. I met regularly with engineers, the product manager, copywriter, design producer, and UX researchers to work through challenges and explore potential solutions.

As I worked on expanding Smart Lock, I kept running into my bias towards designing a screen interface. But the best design is as little design as possible, and sometimes, the best products don’t need much screen-based design at all. In a peak-screen world, this can be magically liberating.

As luck would have it, Golden Krishna, a key advocate of this methodology and author of the seminal book about it, happened to visit Google to give an inspiring tech talk while I was there.

He spoke about how, as designers, we're taught to guard against faulty and premature assumptions—about who our users are, for example (and in my opinion, non-data-validated personas is a key transmission vector for this), or about what is or isn’t technically possible, just to name a few—but we gloss over one of the biggest choices we make as we design products: the choice to take the user's time and visual attention in interacting with our product for granted.

“The real problem with the interface is that it is an interface. Interfaces get in the way. I don’t want to focus my energies on an interface. I want to focus on the job.”

— Don Norman, Director of the Design Lab at UC San Diego

Often, the best interface is one that isn’t an “interface”

It’s technology that’s natively anticipatory. It relies on preexisting, passive signals, like presence, as first-order interaction methods, not obtrusive user action. It’s not an interface.

The benefits of this approach are innumerable, from saving the user time, avoiding entirely the myriad of accessibility concerns in all visual interfaces, and opening up new possibilities in how we can design experiences that make people feel at home wherever they are.

“Good design is innovative...Good design is unobtrusive...And most of all, good design is as little design as possible...[design that’s] less but better.”

— Dieter Rams, 10 Principles for Good Design