Rethinking management of pediatric type 1 diabetes

for

Fuel

A type 1 diabetes diagnosis can be intimidating for anyone, but in pediatric cases, it’s even more so. How can we improve a child’s adherence to taking prescribed insulin? And how can we better educate new patients—and parents—along the way?

A quick note about financial case studies

The designs below are concepts that include placeholder, randomized data for illustrative purposes. Any similarity to real life events are purely coincidental. Nothing contained herein is or should be construed as investment advice, legal advice, solicitation or encouragement to conduct any financial transaction, advertising for any current or future offering of any token or security, or knowledge of a company's future token or security offering plans.

This project was independently produced for BCG Digital Ventures over a short design sprint.

.avif)

What is Type 1 diabetes?

Type 1 diabetes is a chronic condition in which the pancreas produces little or no insulin, meaning that the body can’t properly store and use the glucose it needs for energy.

Insulin acts like a key to open doors within cells so that they may absorb glucose. Without this insulin, cells can’t access the glucose in the bloodstream, causing them to resort to breaking down fat at a high rate instead in a condition called diabetic ketoacidosis, or DKA.

Most people (about 90-95%) of people have the other kind of diabetes, type 2, but what makes type 1 diabetes so difficult is that it’s nearly impossible to prevent, so healthcare solutions need to focus on management. Type 1 is also more prevalent amongst young children, presenting special concerns about management.

.avif)

Medicine

Managing type 1 diabetes in children is a unique challenge

Managing diabetes means eating a consistently healthy diet. And often, it requires regular blood tests and injections several times a day, too. These are all things that most children find difficult and unappealing. And it’s even harder in the early days after a diagnosis, when the lifestyle changes required are new and scary.

Generally, diabetics must determine up to 15 minutes in advance the amount of carbohydrates they’ll eat, take a bolus insulin dose and wait for it to kick in before eating. But it can be hard to predict in advance how much or what a child will want to eat.

This presents one of the challenges and opportunities with health tech. While we might try to solve dosing issue in the technology experience, we could perhaps solve it more effectively with a pharmacological change. Some insulins, like Fiasp, can be taken after a meal, meaning that parents or patients can dose with more confidence.

Further reading: Management of Type 1 Diabetes in Children, by Michael Wood, MD

.avif)

Product Strategy

For ages, parents have had to use finger pricks and injection needles to manage their child’s type 1 diabetes. Fortunately, there’s now a much better, automatic way to do this.

There are essentially three ways to treat diabetes:

- Fully manual: finger prick blood tests at least four times a day, injections at each mealtime (bolus) and once a day additional (basal)

- Semi-auto: some parts of the process can be automated, such as the blood testing component with continuous glucose monitors, or CGMs, and insulin pumps, which dispense insulin into the body through a tiny tube (catheter)

- Fully automatic, hybrid closed-loop systems: these systems automate nearly all parts of the process, automatically adjusting insulin dosing based on CGM readings in real time

This last option, a hybrid closed-loop system, represents one of the biggest advancements in diabetes management ever and it’s was only approved relatively recently (in March 2019) for use in children under age 14. A truly modern solution to managing type 1 diabetes should be built upon such technology, requiring user intervention only where necessary.

What does it mean to design for children?

At the start of this project, I looked for research on designing for child users. Research on this can reach counterintuitive conclusions. Our primary users are those age 8 to 12, an age by which children are considered pretty experienced with interacting with technology, but research also shows that without clear direction, users at this age are likely to find apps without clear direction confusing.

But designing in a way that gives the user as much understanding of the path ahead is good design anyway. As I discovered, children at these ages don’t as much require a different experience as much as they’re less forgiving of suboptimal experiences. Their attention spans can be shorter and we can be less confident that they’ll know how to overcome a confusing state. Designing for these constraints is more than just good for children—it’s good for everyone else, too.

UX research for children has to consider delivery platforms as well. On average, children in the US get their first smartphone at around age 10.3. That leaves the lower bound of our target age demographic as relatively unlikely to have such a device that we might use to deliver a product experience on. But on parenting blogs, the primary reason behind giving a child a smartphone is need, and 10.3 is just the age at which most parents see this need.

For our users, type 1 diabetics, the value proposition of being able to manage the condition better is significant and, I suspect, a reason to consider that this age might be lower for this population.

.avif)

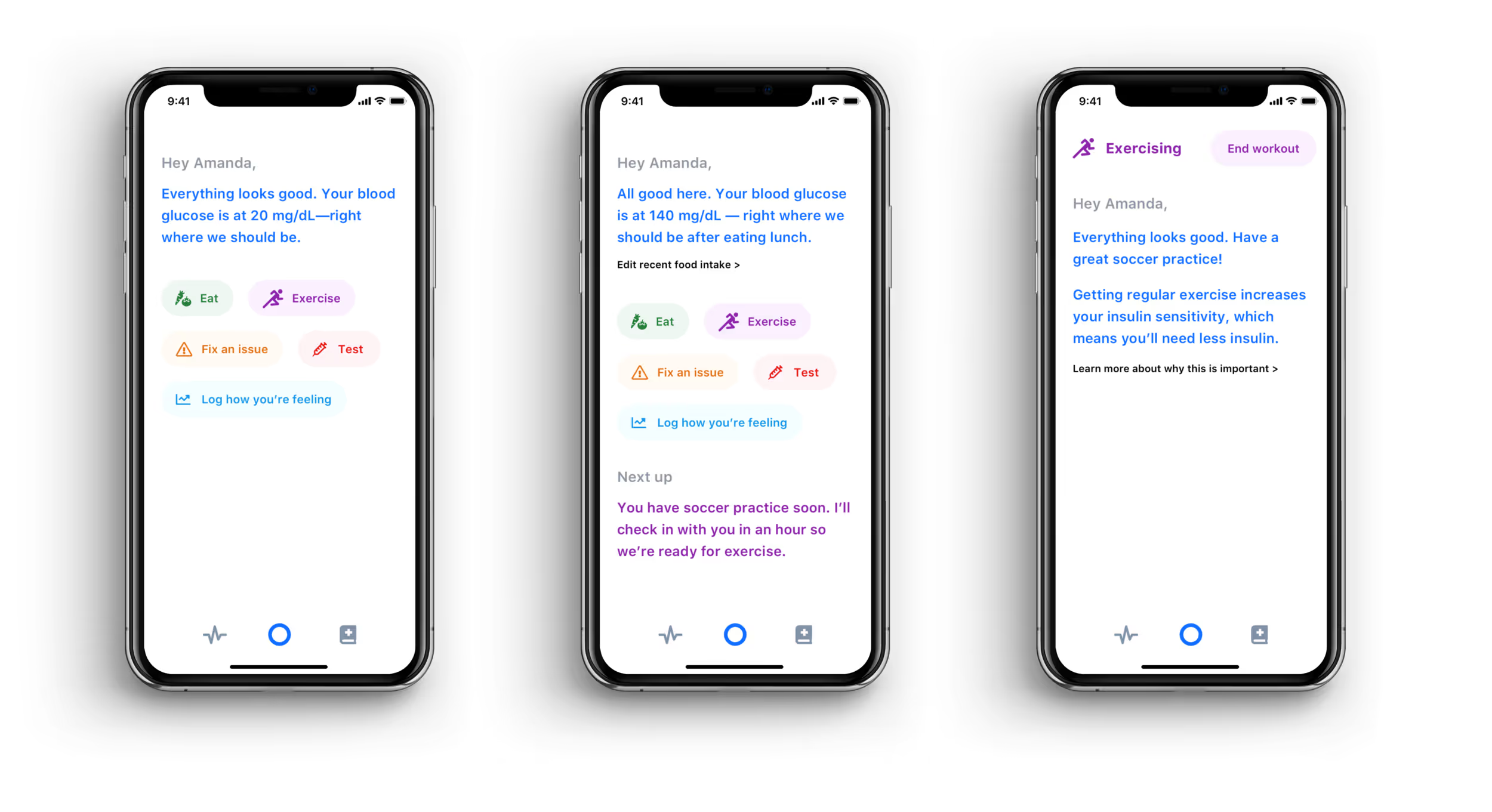

Though the automated system can test blood and administer insulin automatically, it can’t know if the child is about to eat or exercise without the child’s involvement.

How might we reliably get this critical interaction from a user who’s likely to have a short attention span, be otherwise engaged, misunderstand the seriousness of situations, and/or require very clear direction?

Product

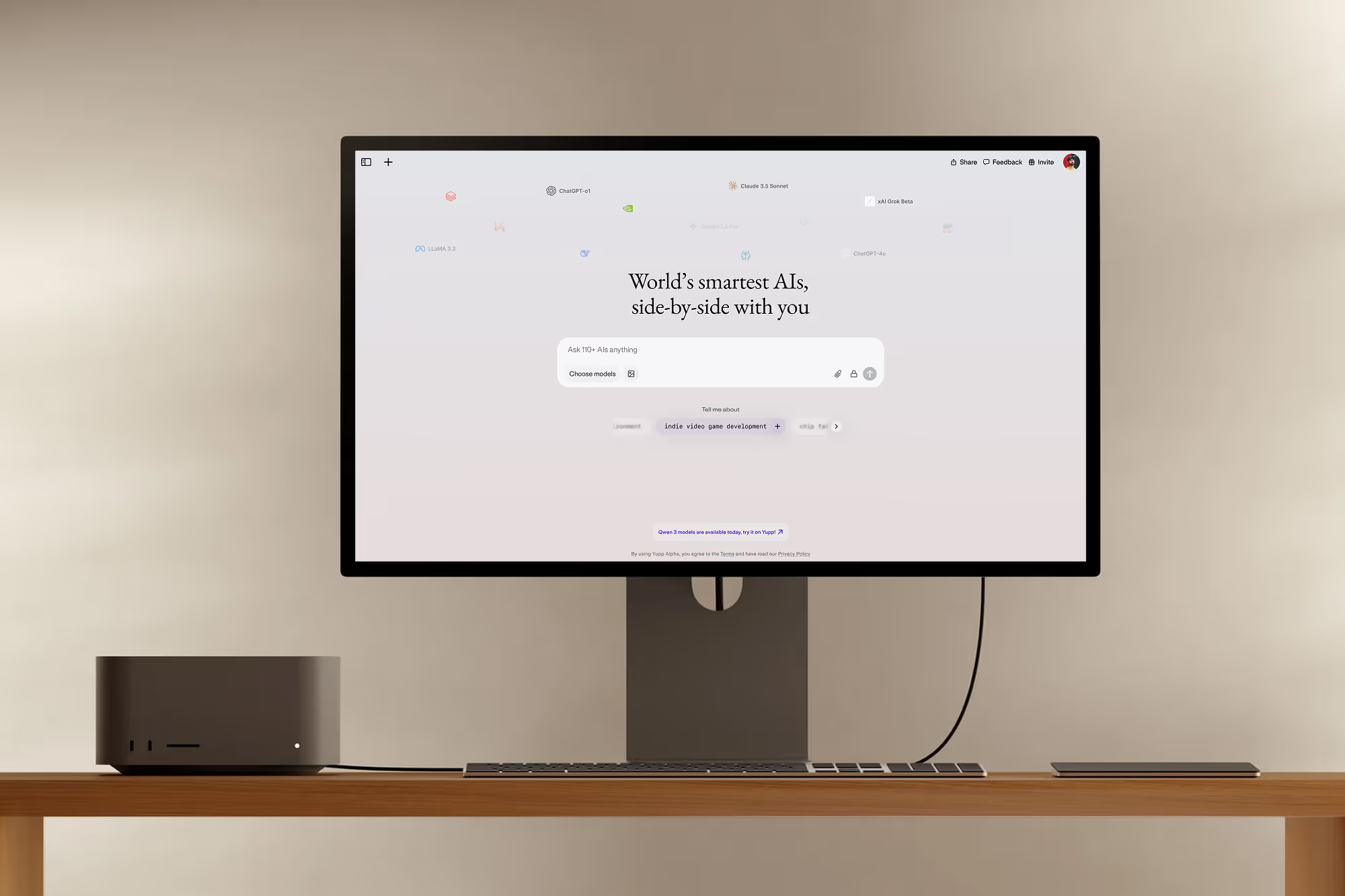

Assistant UIs are ideal for unstructured, adaptable, fluid experiences that involve close, routine, and bidirectional interaction between humans and machines

I considered delivering this assistant experience in a more conversational UI—with chat bubbles as you’d expect on a messenger app, but this ended up feeling too contrived and superfluous for this application. It also set up a metaphor wherein the user would be able to type or speak to a chatbot directly, and this again felt too complicated for our target age demographic. It would allow too many edge cases and too much opportunity for interaction. Users would be seen to be “texting” throughout the day, creating an issue in a school environment where such devices are often off limits unless truly needed.

Moreover, this interaction is less open ended in terms of user generated content than true assistants, like the Google Assistant or Siri are, and five action buttons are sufficient for the user to express their intent.

Let’s see how Fuel can help Amanda, from waking up to afternoon soccer practice:

We’d like to help a child through their day, but technology can fail, and so it’s essential that they learn how to manage their diabetes without the app as well. To that end, everything the assistant does is accompanied by educational explanation to teach and reinforce the link between adherence to one’s diabetes management plan and feeling/doing well. We want to make as explicit and short as possible this feedback loop between behaviors and outcomes.

How? Just as the best way to design is with, not for, so too does the assistant work with, and not for, the patient. This also ensures the patient is always in the driver’s seat, a particular concern as the child grows up and desires more autonomy and responsibility.

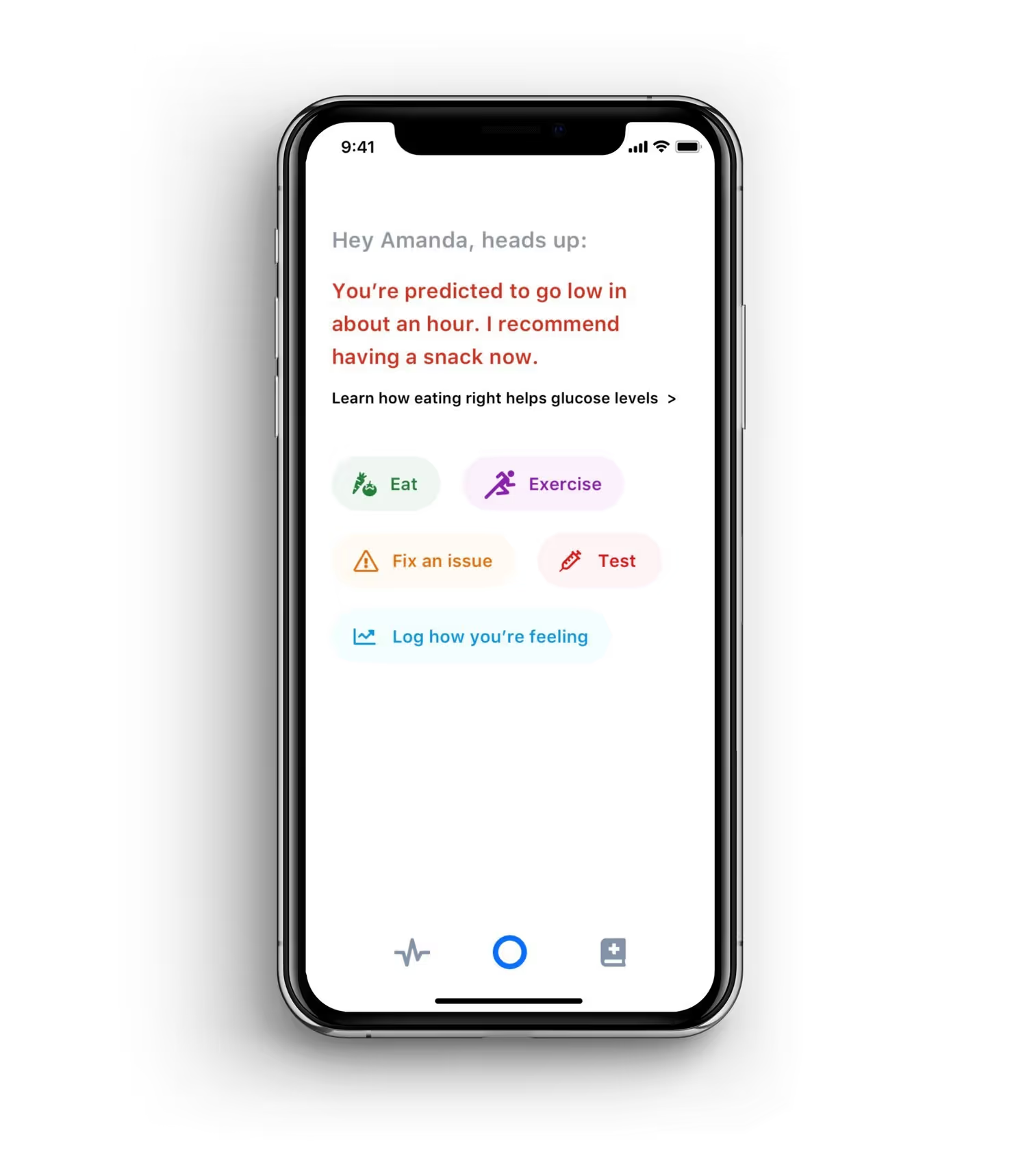

Usually, everything will go according to plan. But when it doesn’t, it’s critical we handle it properly.

Current hybrid closed-loop systems and CGMs provide similar warning functionality to this, but lack educational prompts alongside the alarm, so the child needs to know what to do, and in a stressful situation. With Fuel, natural language instruction makes it clear.

Visual design cues like red text also help contextualize that this is something that requires immediate attention.

Messaging and Brand Voice Principles

For an assistant, getting the right tone of voice in the messaging is critical to encouraging adherence

Assistants are supposed to help, not police, but for the critical tasks surrounding diabetes and the age of the user (primarily 8-12 years old), this was a tough balance to find. It’s essential to convey the importance or urgency of tasks while not sounding as if it’s nagging or policing the user. The following principles helped to guide the narrative voice:

Freedom and responsibility go hand in hand. The user is always in control, but that also means that the user is always responsible.

People rarely object to being treated firmly if it’s fairly. In research, I reached out to a teacher with decades of experience teaching our demographic bracket. He emphasized this aspect of framing requirements as opportunities to take personal responsibility and so therefore, personal freedom.

My work alongside Google’s user controls and trust team taught the importance of this principle, too.

A friendly, conversational, honest tone sets up a collaborative relationship in which respect goes both ways. The assistant is a friend, but also a coach.

Tone is perhaps the most critical signal of a relationship. I considered a more formal tone, like a doctor might have, but decided that with something this omnipresent and personal, it would make more sense to just cut to the friendly relationship. I suspect it increases the likelihood of honesty on the part of the user as well.

Taking insulin, just like eating healthy food, are just components of "fueling" your body, and when you fuel better, you feel better.

By tying insulin adherence, food logging, etc. to how the user feels and performs, they’re motivated to stay on track. After all, one of the reasons pro athletes perform so well is how focused they stay on their regimen.

When you eat properly and take your insulin, you feel better and can do more.

Nightly Promise

But treating diabetes isn’t just about nutrition, testing, and dosing. There’s a powerful psychological component as well.

Parents are often concerned that their child’s blood glucose will drop too low overnight—something called nocturnal hypoglycemia. With traditional blood testing methods (finger pricks), symptoms may not be realized until the child wakes up to sweaty sheets, a headache, excessive tiredness, and even memories of bad dreams. In other cases, it can be even more serious.

New hybrid closed-loop systems dramatically reduce this risk. They can automatically adjust the basal insulin dose to compensate if the continuous glucose monitor (CGM) predicts blood sugar is about to go low, or in rare cases, sound the alarm to a parent if it’s unable to prevent hypoglycemia.

But being safe isn’t the same as feeling safe. Even though they may know it’s safe, people will check whether they’ve locked the door, turned off the gas on a stove, or in the case of children, if there’s a monster under the bed.

How can our technology go beyond simply keeping us safe to actively reassure us that we are? In managing diabetes, this psychological aspect can be one of the hardest pieces of the puzzle to solve.

Nest Protect, a smart smoke and CO detector, has a great feature called Nightly Promise. Each night, when you turn off the lights, Protect’s center ring glows green to reassure you that it’s working properly and keeping you safe as you drift off to sleep.

Could we offer children with diabetes something similar? For children with diabetes, their nightly routine could include a promise that they’re safe when the bedtime story ends and the light is switched off.